Tell The Truth

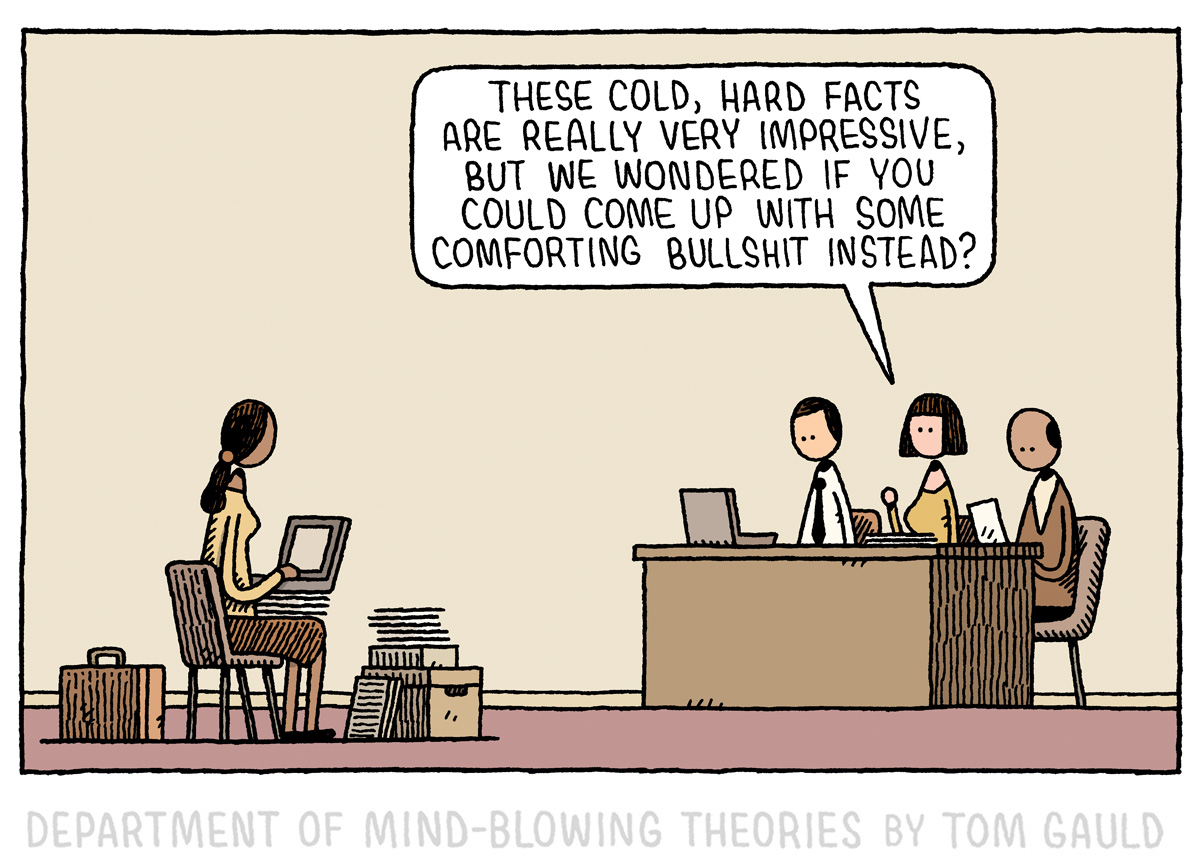

A year ago, I left the corporate world. I was happy to leave it, for a number of reasons. I did not believe in capitalism. I perceived my bosses as ill-intentioned, or at best amoral. I perceived my colleagues as amoral, or at best nihilist. The office environment was oppressive in a thousand ways. But perhaps more than anything, I hated the bullshit.

If you’ve ever worked a corporate office job, you probably know what I mean. The glossy marketing materials promising a product that “will transform your industry”, when you were on the team that built that product and you know it doesn’t really work yet. The lengthy motivational speeches from senior management, where afterwards the employees look at each other wondering, what exactly did they say? (Nothing. They said nothing. They just talked at us for a long time.) The ever-increasing amount of bullshit generated by capitalism is like an epidemic.

XR was a perfect antidote to that, a breath of fresh air. It said tell the truth. It complemented a lightweight, succinct, and elegant ideology with hilarious, clever, and effective actions.

My decision to join XR was the right one. But by joining XR on an almost full-time basis, I was jumping into the deep end of a world with which I had only a passing familiarity – the occasional strike or demonstration I had participated in as a student – the world of activism. And to my surprise, it turns out there is almost as much bullshit in this world as there was in my previous world. Although the specifics of the bullshit are different, the bullshit-generating mechanisms are similar.

What is bullshit? You might yell “bullshit!” when someone says something you disagree with. But bullshit is actually a technical term, a category of speech that has been studied by philosophers. Synthesizing what I’ve read about the subject, I will work with this definition:

- Bullshit is a use of language that purports to convey factual information, but actually intends to convey something else.

To convey a vibe. A feeling. An emotion. A marketing slogan. In bullshit, what matters is not the content of the statement, but the form.

Now, you might wonder, is it always bad to use language for such a purpose? What if your favourite poem conveys less practical information than a recipe for chicken soup? Does that make it bad? Of course not. Technically, it might be bullshit, but not all bullshit is bad, or even meaningless. Bullshit is part of culture. Human life without any bullshit is unimaginable. From song lyrics to stoner conversations, a little bit of bullshit can go a long way to making life liveable.

But in the fight against climate change, we must be fundamentally committed to the truth. The real truth, the objective truth, the scientifically verifiable truth. Not, to use Roger Hallam’s expression, the “post-modern truth” of public opinion. We are committed to fighting the bullshit of capitalism, of our so-called democracies, of infinite growth on a finite planet. To be an environmental activist is to be militant against bullshit.

Here are some examples (and counterexamples) of bullshit. I am to some extent guilty of conflating rhetorical fallacies (statements that have meaning, but are logically indefensible) with classical bullshit (statements whose content is eclipsed by their form). This is a bit sloppy, but hopefully good enough for a blog post. The idea is that if the content of your message is not its most important feature, then it’s bullshit. The counterexamples hopefully illustrate that a statement can be stupid or factually untrue without being bullshit.

| Example | Category | Is it bullshit? |

|---|---|---|

| “If you don’t join my cult, then you are a bad person” | Guilt by default | Yes. If everyone is guilty by default, then any statement about guilt becomes meaningless. |

| “I don’t know if 5G is dangerous, but it makes me feel uncomfortable, so it should be banned” | Appeal to emotion | No. The statement is stupid, but it conveys an actual opinion. |

| “What you’re saying is true, but this is the wrong time to say it” | Appeal to decorum | No, because the statement conveys an actual opinion. But if the speaker thinks there is a “right” and “wrong” time to tell the truth, then they are probably susceptible to bullshit. |

| “Handing out speeding tickets is pure fascism” | Moral equivalence | Yes. Speeding tickets are annoying, but not as annoying as fascism. |

| “I once bought a solar panel that was made by child labour, therefore, solar panels are not a sustainable energy source” | Non sequitur | Yes. The conclusion doesn’t follow from the premise. |

| “To raise my awareness of my own complicity in oppressing animals, I will henceforth only read novels whose protagonist is an animal” | Virtue-signalling | Yes. The goal of the statement is to signal the speaker’s righteousness. |

| “Had the criminal been Black, the journalist would have never portrayed his vulnerable human side” | Assuming bad intentions | Yes. The speaker has no idea what the journalist would have actually done, had the perpetrator been Black. |

| “Everyone and his dog has a single-speed bike these days” | Exaggeration | No. The statement conveys an opinion about the popularity of single-speed bikes. |

| “That argument plays into the hands of climate-deniers, you must be a shill for the oil industry” | Guilt by association | Yes. Also an example of “assuming bad intentions”. |

| “My XR chapter is so inclusive, every single person in my town is a member” | Appeal to popularity | Yes. The goal is stopping climate change. Just because you’re popular, doesn’t mean you’re having an impact. Eyes on the prize! |

How can you avoid committing bullshit, and how can you fight bullshit committed by others? When you say or write something, ask yourself: what is the meaning of my statement? Is it clear and unambiguous? What is the information that my statement conveys?

Conversely, when someone else makes a statement, ask yourself the same questions. What are they actually saying? If you’re not sure, ask. The only risk of asking is that you might appear ignorant. The risk of not asking is that you will be ignorant.

In order to decide whether a statement is bullshit, here are some tips & tricks. Consider a candidate statement. Suppose you agree (respectively, disagree) with it. Negate the statement: for example, replace “is” with “is not” or “all” with “none”. Do you now disagree (respectively, agree) with it? If not, then either the statement is bullshit, or you didn’t understand it. Either way, clarification is needed. Another trick, popular among elementary school teachers, is to “rephrase in your own words”. For example, if after reading this post, you cannot close your eyes and summarize it in a sentence or two, it means I have bullshitted (or you have failed at reading). Perhaps the greatest trick of all is to simply ask for evidence: does 5G really cause cancer in laboratory rats? Show me the peer-reviewed paper that says so. If you can’t: it’s bullshit.

I mentioned above some blanket exemptions, uses of language that might technically qualify as bullshit, but not in a bad way. We might want to add another exemption here. Consider that the success of XR as a global movement is, at least in part, due to its branding. The name Extinction Rebellion, the typeface, the hourglass logo, the colour scheme, and so on. All these things are visually compelling. They are, technically, a type of bullshit. Generated not to convey information per se, but to convey a vibe. By volunteers, by activists, by artists – some of whom might actually have corporate branding backgrounds. Start with the name, Extinction Rebellion: do we really think every single human is going to disappear if we don’t stop global warming? Or merely 95% of humans? We just don’t know. And yet we confidently say Extinction. Is that bad? I’m not sure. Most of the time, I think it’s OK.

I guess I’m biased, because I love this movement, and I hope it will succeed. If we succeed, it will be by collective action. As individuals, ultimately, we are all powerless: the strength of our movement is in cooperation. In order to cooperate effectively, we have to communicate well. Bullshit (for the most part) just gets in the way of good communication. To this end, I propose an 11th Principle of XR:

- Avoid bullshitting, and call out bullshit when you see it.

We don’t have to add Principle 11 to our website. It can be a virtual principle. Keep it in mind. Next time you’re in a meeting with me, and I say something that smells like bullshit: please call me out on it. I might defend my statement, but I promise not to be offended. As a Rebel in XR, I am committed to the first demand: tell the truth.

Thanks to the Internet for types of rhetorical fallacies which I repurposed in the Category column of the examples table